Lumbar Spinal Stenosis

What is lumbar spinal stenosis?

In general, lumbar spinal stenosis represents a variety of structural changes that contribute to narrowing of the space within the bony spinal column where the spinal cord and/or nerve roots are located. There can be narrowing (stenosis) in the central spinal canal where the spinal cord and nerve roots are located, which is called central canal stenosis. Alternatively, there can be narrowing of the spaces on the sides of the spinal canal (lateral recess or foramen) where the nerve roots that branch off the spinal cord exit before then moving toward the lower limb. Central, lateral recess, and/or foraminal stenosis and resulting spinal cord and/or nerve root impingement can cause a variety of symptoms such as pain, weakness, numbness, or tingling at the low back and into the hips, buttocks, and lower limbs.

What causes lumbar spinal stenosis?

In most cases, the development of lumbar spinal stenosis is multifactorial. With time, disc bulges or herniations, malalignment of the vertebral segments (spondylolisthesis), osteophyte (bone spur) formation, enlargement (hypertrophy) of facet joints, and ligamentum flavum thickening may all gradually contribute to a narrowing of the spinal canal. In addition, some people are born with shorter pedicles and, thus, are considered to have congenital spinal stenosis. Finally, in rare instances in which a person suffers a significant acute injury, a large disc herniation may cause a more rapid onset cervical spinal stenosis.

How is lumbar spinal stenosis diagnosed?

A diagnosis of lumbar spinal stenosis is primarily based on a patient’s symptoms and physical examination findings. Typical symptoms and signs of lumbar radiculopathy include low back pain with radiation of pain to the buttock, hip, thigh, or lower leg. Additionally, there may be associated weakness, numbness, tingling, or reflex changes. One important feature may be neurogenic claudication which is the onset and worsening of pain, weakness, numbness, tingling, “heaviness,” or fatigue sensation in the hips, buttocks, and lower limbs that is exacerbated with standing and walking, and improved with sitting or leaning forward on an object such as a shopping cart or walker. Finally, advanced imaging (MRI or CT) and/or electrodiagnostic testing (EMG/NCS) may help to further solidify the diagnosis.

How is lumbar spinal stenosis treated?

Initial treatment options for management of lumbar radiculopathy or radiculitis due to lumbar spinal stenosis may include medications, physical therapy, and/or chiropractic. In many cases, these conservative measures will allow for good recovery. If a patient is still experiencing significant pain despite the aforementioned treatment options, a lumbar epidural steroid injection can be considered as the next step in the treatment pathway. Finally, when all typical non-operative treatments have been exhausted and a patient is still experiencing significant pain, a referral to spine surgery may be considered for further evaluation and possible surgical intervention. In cases where a patient does not wish to pursue surgical management or may not be deemed a good surgical candidate, spinal cord stimulation may be utilized to help provide relief of pain and improvements in overall functional status.

Epidural Steroid Injection

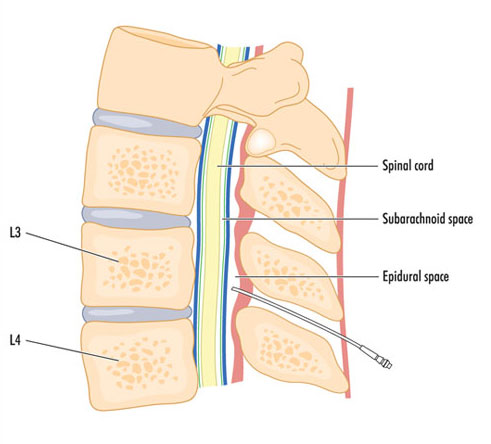

When patients with lumbar radiculopathy/radiculitis due to disc herniation have not significantly improved with conservative treatments such as medications, physical therapy, or chiropractic care or are unable to tolerate their rehabilitation due to severe pain, an epidural steroid injection (ESI) can be considered. Using x-ray (fluoroscopic), a needle is carefully and precisely guided to the epidural space. Once the epidural space has been accessed, a steroid solution is instilled through the needle and coats the inflamed and painful disc herniation and nerve(s). This helps to decrease inflammation and, subsequently, decreases pain and improves function.

Recent systematic reviews have demonstrated high quality evidence for use of ESIs for management of lumbar radicular pain. In the hands of a fellowship-trained interventional spine physician like Dr. Best, ESIs have been found to provide good to excellent improvement in pain in both short- and long-term periods.

While it is not intuitive, studies do not demonstrate any added benefit with a higher dose of steroid. Use of lower dose steroid with an ESI has been shown to be just as effective as moderate and high dose steroid.

As it stands right now, there is no conclusive evidence regarding the number of ESIs that can be performed in a year or a lifetime. However, appropriate spacing between injections and close monitoring of cumulative steroid dosing is important. While a total dose of corticosteroid that a patient receives must be accounted for including oral medications and other injections (e.g. knee injections, shoulder injections), Dr. Best generally limits injections that utilize steroid to 3-4 per 12-month period and separates them out by at least 2-3 weeks.

The response to ESIs can be variable. Some patients may only require one or two ESIs during their entire lifetime to help manage an acute pain issue and may never experience another bout of neck or back pain. Some may experience occasional exacerbations of their cervical or lumbar radicular pain which may require additional injections. The care is tailored to each individual patient and set of circumstances.

The beneficial effects of an ESI usually take effect in 2-7 days after the injection; however, this may be as variable as 1-14 days for some patients.

The large majority of patients do not experience significant side effects from ESIs; however, short-term and generally short-lived side effects may include increase blood sugar (glucose) levels, flushing, insomnia (difficulty sleeping), and gastritis. Long-term side effects of excessive use of steroid may include hypothalamic-pituitary-axis suppression and Cushing’s disease. Dr. Best is mindful of potential excessive corticosteroid administration and is judicious when it comes to this issue.

Steroids administered with ESIs have the potential to increase blood sugar (glucose) levels. On average, blood glucose levels may be increased for one day in non-diabetics and 2 days for diabetics; however, blood glucose levels may be increased for 7-14 days in diabetics. As such, patients with diabetes must do their best to obtain good glucose control prior to an ESI (ideally maintain a hemoglobin A1C less than 7%), monitor their blood glucose levels very closely after undergoing an ESI, and the blood glucose level must be 200mg/dL or less when checking blood glucose level prior to the injection. If an increase in blood glucose levels is noted after undergoing an ESI, it is recommended that the patient contact their primary care physician or endocrinologist to discuss short-term management strategies of the elevated blood glucose levels.

Currently, there is no significant evidence that avoidance of bathing or swimming decreases risk of infection after spine injections; however, we generally ask that patients avoid submerging in water for 24 hours after the injection just to be on the safe side. There are no concerns regarding showers at any point after an ESI.

Spinal Cord Stimulator

A spinal cord stimulator (SCS) is a non-surgical, minimally invasive treatment for chronic lumbar radiculopathy/radicular pain that uses electrical impulses to block specific nerves of the spinal cord that transmit pain. It consists of a pacemaker-like battery pack called a generator and thin wires called leads. Together, the generator and leads produce electrical signals that stimulate specific nerves of the spinal cord which mask or modify pain signals before reaching the brain, thus greatly diminishing a person’s interpretation and perception of pain.

SCS may be used for patients who have chronic pain conditions despite trials of treatment options such as medications, physical therapy, chiropractic, injections, and even surgery. Indications for use of SCS include chronic low back or neck pain with or without limb pain such as failed back surgery syndrome (post-laminectomy pain syndrome). It may also be used for patients with chronic nerve pain conditions such as complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS), painful peripheral polyneuropathy, or painful diabetic neuropathy. Finally, SCS may be used for those patients with chronic pain who may not be surgical candidates or those who wish to avoid surgery altogether.

If a patient is deemed to be a good candidate for a SCS, Dr. Best will discuss performing a trial first. During a SCS trial, the epidural space is accessed using an introducer needle and x-ray (fluoroscopic) guidance just like an epidural steroid injection. However, rather than instilling steroid through the needle, a very small and thin wire (spinal cord stimulator lead) is inserted into the epidural space and gradually advanced to the mid-thoracic region. The other end of the leads exit the skin at the site oof introducer needle placement and connected to the generator which will be secured to the patient’s flank area during the 5–7-day trial period. During this 5–7-day period, the patient has the opportunity to test out the SCS technology and get a sense of whether it helps to significantly decrease pain and improve function. The patient then returns to Dr. Best’s clinic to discuss the result of the SCS trial. During the follow up visit in clinic, the SCS trial leads are removed and, if successful, the patient may choose to have the spinal cord stimulator permanently placed. When a SCS is placed on a permanent basis, all components of the leads are once again placed in the epidural space and advanced to the mid-thoracic region; however, they are then tunneled under the skin and connected to the generator which is sitting in a subcutaneous pocket created with a small incision.

The common goals when considering the use of SCS include significantly decreasing pain, decreasing need for and use of pain medication, and improvement in overall function.

At a Glance

Dr. Craig Best

- Harvard Fellowship-Trained Interventional Spine & Sports Medicine Specialist

- Double Board-Certified in Physical Medicnie & Rehabilitation and Pain Medicine

- Assistant Professor of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation and Orthopedic Surgery

- Learn more